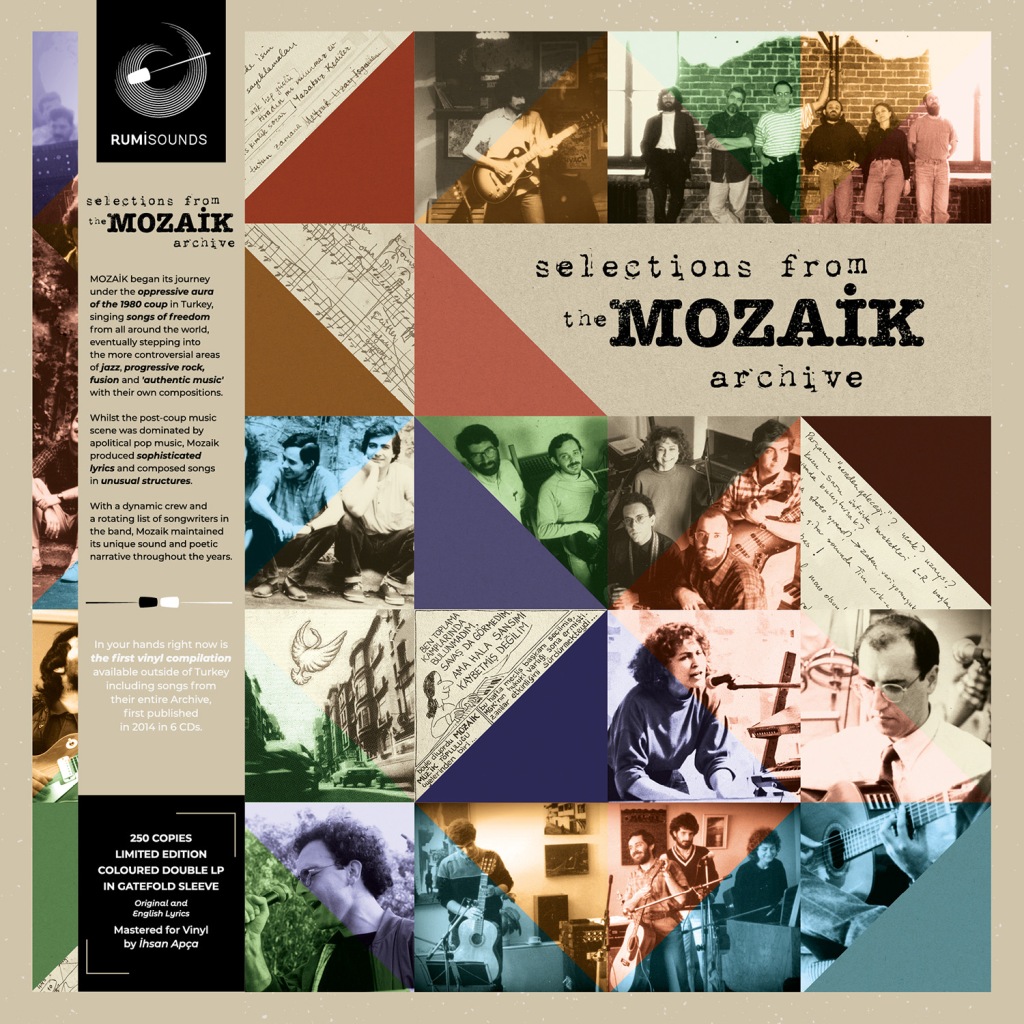

180 gram coloured double LP in gatefold sleeve

MOZAİK began its journey under the oppresive aura of the 1980 coup in Turkey, singing songs of freedom from all around the world, eventually stepping into the more controversial areas of jazz, progressive rock, fusion and ‘authentic music‘ with their own compositions.

Whilist the post-coup music scene was dominated by apolitical pop music, Mozaik produced sophisticated lyrics and composed songs in unusual structures. With a dynamic crew and a rotating list of songwriters in the band, Mozaik maintained its unique sound and poetic narrative throughout the years.

Linear Notes (by Erdir Zat)

We Owe Mozaik

It was the last days of 1980. A friend and I were walking from the Deniz Park tea garden behind the Ortaköy Mosque to the bus stop. It was almost twilight. As we turned the corner to exit the square, we came face to face with the patrolling blue-beret gendarme commandos. They halted us. We knew their sergeant from the stop-and-searches we had come across before. I thought we would go through such a search-scan-identification routine again. I remember instinctively trying to get my ID card out. Within seconds, they had both of us grabbed and laid face down on the ground. Before I knew what was happening, I felt the cold metal against my neck. It was the barrel of the G3 automatic rifle. It was the first time I encountered such a thing. Throughout my life, I have been able to re-enact this complex emotion, which I have never been able to name fully. The state had threatened me with death. I was sixteen.

Those who live their early youth in the eighties are unfortunate. Probably no generation has been as frightened as we are during adolescence. We were the laboratory subjects of the September 12, 1980 regime. We have been painstakingly intimidated by applying large-scale systematic methods developed especially for us. We were the first on the to-do list; When we reached university age, the YÖK (Board of Higher Education) was already in place. For those who were outside the sphere of influence of their fascist propaganda in the form of mass worship, life was doubly difficult. We had no alternative. So, the mood of the eighties was primarily one of gloom, a deep anxiety. This is how we discovered existentialism. We had to embark on an inner journey that contrasted with our age. Kafka’s dark humour gave us breathing space. Perhaps the only accomplishment of the September 12 period was the hundreds of books and the same amount of music we hugged to overcome the depression. There was nothing else to do. We really had no alternative.

Mozaik emerged in such a social climate. They sounded an invitation to scatter the dark clouds that have blanketed our lives, and they voiced it as early as 1983, at the best possible moment: Ölümden Önce Bir Hayat Vardır, the name of their first concert was a translation of Wolf Biermann’s song, Es gibt ein Leben vor dem Tod (There is a Life Before Death). This concert album consists of folk songs concerning life, in different languages, compiled from different regions of the world. The album (not yet an album, a bootleg recording on cassette tape) had become legendary in the scattered counterculture of the first half of the eighties. Many of us, who got the clean recording much later, listened to the album from bad copies made from cassette to cassette. I can never forget that one of the copies I came across was recorded over on a Selami Şahin cassette. In this respect, it was one of the pure underground products of the September 12 era.

Later Mozaik albums revealed that the first album was actually a very special one. Normally, such cover albums are made as some kind of a fantasy, long after the band has established its own character and settled down. The fact that the opposite happens in Mozaik has always seemed like an important detail to me. Because Mozaik is first and foremost a project group. The members of the group, each of whom has different musical tendencies, and some of them also express themselves in areas other than music, are volunteers who bring projects to life, sometimes as a commentary on a song, sometimes as a small vocal contribution, sometimes as a whole album. This feature of Mozaik did not change when it took a more formal group appearance. A careful Mozaik listener could usually guess whose project a piece they have just listened was (except Kuzu’s songs, of course; he always managed to surprise.)

On the other hand, no matter whom the project originally belonged, it was always worked out together; collective creativity was the quality that made Mozaik a group. Mozaik doesn’t have an ordinary, identifiable ‘Mozaik sound’, but we can speak of a more general stylistic integrity that keeps this experimental music workshop’s feet on the ground. The masterpiece Kör Uçuş (Blind Flight) in their first studio album that will never get old, Ardından (And Then… 1985), could be the best example of this binding force, followed and crosschecked by Onüç (Thirteen)…

“What is Mozaik’s genre?” This question was either answered in a cascade of unrelated music genres, or left unanswered. From today’s perspective, it is probably not that complicated: Considering all these qualities above, Mozaik is clearly a progressive rock band. Like many progressive rock bands with whom we can connect it to, it travels across genres; subjects its constitutive elements to cold or hot fusion. Isn’t what we call ‘rock’ a kind of fusion, anyway? In doing so, however, Mozaik is not only eclectic, but also authentic in the truest sense of the word. It seems to be saying, “This is the only way we can understand today, so we can only represent it thus.”

Since I already have contradicted my principle of not writing in the first person singular, let me at least enjoy it with more personal comments. When I look at it again today, I see Mozaik’s opus most similar to the work of Robert Wyatt, the big heart of Soft Machine. Musical similarities aside, I’m talking about the universality that we find in Wyatt, a sense of belonging to the common human culture in the way it is processed. The thing that impressed us most when we listened to Mozaik’s Ardından, which was the first example of its own style, was universality. What we were listening to was categorically related to the universe of Pink Floyd, King Crimson, Frank Zappa. The albums Çook Alametler Belirdi (Many a Sign Appeared, 1988) and Plastik Aşk (Plastic Love, 1990) reinforced this feeling. At that time, however, we were content with the feeling that “So we can do it too!”, since the concepts to describe and elucidate this feeling did not yet exist. The We here was important, because Mozaik, besides all its universal qualities, was a local group after all.

The September 12 coup cut the lifeblood of a young and dynamic society, full of hope and excitement. The huge cultural accumulation of the 70s couldn’t be transferred to the next generations. The fact that the Anatolian Rock movement became popular again in the 2000s, at least twenty years after it was a living movement, is an indicator of this bitter truth. From the fifties to the present, rock in the West has progressed uninterruptedly through successive currents and undercurrents. The history of rock is knitted with the cause and effect connections between these movements. The coup was a ruthless sword blow for us. If life had followed its normal course, the successors of the Anatolian Rock movement should have emerged in the 80s, should have settled the action-reaction showdown with the 70s, and continued on their way. Since the existing infrastructure was destroyed, the 80s generation had to deal, willy-nilly, with rebuilding in all cultural areas. This historical interruption is one of the most important reasons why Mozaik is an unprecedented group and, to a large extent, with no successors, although it has influenced many valuable groups that came later.

Mozaik is a timeless group in every sense of the word. If we look at its musical preferences, it actually represents a reaction to previous musical movements. But since the context for discussing these issues was removed, it could not find the chance to express its criticism on the spot. It has a very sophisticated comment to shed light on the endless locality-universality debates of the 70s; but there was so much to be said before that, so that its time never came. That’s why Mozaik remains like a desert cactus in our popular music history.

We owe a lot to Mozaik. The reissue of their albums is an opportunity to reinstate Mozaik to the place it deserves. We may not be able to replace the losses of September 12, but we can transmit the gains of a respectable resistance movement to new generations on this occasion. Yes, there was a life before death and we lived it!

All Mozaik Members (1983-1995)

Ayşe Tütüncü: Vocals, Piano, Synthesizers (1983-1995)

Saruhan Erim: Vocals, Guitars, Bass (1983-1995)

Mehmet ‘Kuzu’ Taygun: Vocals, Guitars, Drums (1983-1995)

Timurçin Gürer: Vocals, Percussion (1983-1995)

Bülent Somay: Vocals, Guitars, Electric Guitar (1984-1995)

Serdar ‘Sateş’ Ateşer: Vocals, Bass, Guitars, Electric Guitar (1983-88, 1992)

Mehmet Tütüncü: Violin (1983-1985)

Sumru Ağıryürüyen: Vocals, Mandolin (1983-1984)

Ezel Akay: Vocals (1983-1984)

Levon Balıkçıoğlu: Vocals, Accordion (1983-1984)

Sabir Yücesoy: Flute (1983)

Yağız Üresin: Flute, Alto Sax (1984-1985)

Tahsin Ünüvar: Flute, Tenor Sax, Soprano Sax (1987-1989)

Murat Ünlü: Bass (1985)

Emir Özoğlu: Drums (1984)

Ahmet Altuğ: Drums (1985)

Cem Aksel: Drums (1986-1988)

Ümit Kıvanç: Drums (1988-1991)

Mastered for Vinyl by İhsan Apça